Wisdom and Moral Order

Welcome to the third edition of Faith Seeking Understanding! For those of you who are joining in for the first time, the goal of Faith Seeking Understanding is to equip Christians to develop a biblical worldview, grounded in God’s plans and purposes as revealed in the scriptures, integrated with insights into his creation discovered through various human disciplines, for the sake of knowing and serving him better.

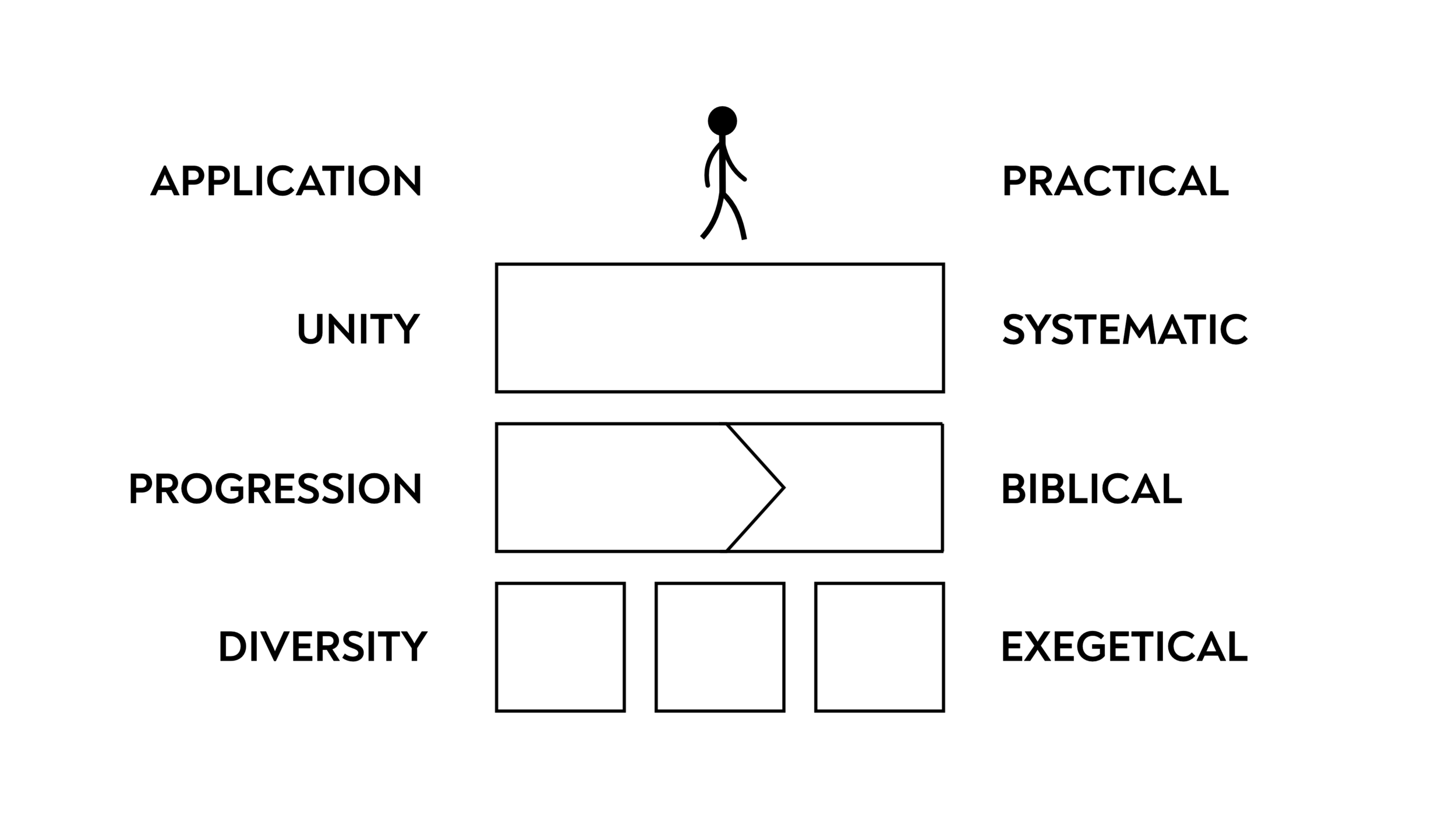

And so far that’s what we’ve been talking about. We spent our first module thinking together about how God’s plans and purposes are revealed in Scripture: the discipline of biblical theology. We thought about the fact that, while we need to read each book of the Bible on its own terms—taking into account things like historical context, working hard to get into the head of the original author as best we can to understand what they meant (and not project our own ideas onto the text)—the Bible is ultimately tells one story.

In our second module we tackled what we call systematic theology, where we combine what we can know from scripture—so the things we learn about in biblical theology—with what we can know from nature to build a system of thought about God and his creation. As with biblical theology, what characterises systematic theology is unity. On any given topic we’re asking the question, What does the whole Bible teach us about this? The difference is that here we have what we could call absolute unity: unity that’s not divided up into slices by time, but timeless truths about God and his creation.

Now, we’ve said already that the goal of Faith Seeking Understanding is to equip Christians to develop a biblical worldview, grounded in God’s plans and purposes as revealed in the scriptures, integrated with insights into his creation discovered through various human disciplines—which so far is exactly what we’ve been trying to do. But why?—for the sake of knowing and serving him better. It’s that last bit that we’ll be focusing on in this module.

In this module we’re looking at what we can call practical theology—thinking together about what it looks like for what we learn on levels one, two, and three of the diagram to shape the human in the fourth level. It’s the next step on from systematic theology to ask the question, in light of all of this, how then shall we live? Practical theology is quite broad, but for the purposes of this module, really what we mean by practical theology is ethics, which, in a nutshell, is the study of how to live well—or, to put it differently, how to live the Good Life.

So where do we start? Our temptation may be to go straight to the NT. The problem I think we’d run into, though, is that the NT what came before it—to understand the NT, we need the OT. We’ll come to the NT later, but to begin with, we’ll spend some time in the OT.

Morality and Old Testament law

So where do we go in the OT? We might be inclined to flip to the “law” parts of the OT—maybe somewhere like the Ten Commandments. The Ten Commandments, after all, are taken by many Christians to be the standard for how we ought to live. Entire books have been written on how they apply to us today, and how we should read them in light of Jesus’ teaching. The bulk of my first year ethics class was basically a long, slow walk through the Ten Commandments.

Where many Christians have gone wrong with the Ten Commandments—and passages like the Ten Commandments, which seem to be instructive for how we live as God’s people—is forgetting to read it in context. Our problem, I think, is that we’re so familiar with how law works in our modern legal systems that it’s hard to imagine how it could be any other way. But there are significant differences between how we understand law today and how they understood law in the ANE. To read the OT properly in its own context, then, we need to spend some time thinking about some of these differences.

Law in the ANE

What it comes down to is the relationship between justice and order on the one hand, and written law on the other. In modern day law codes, these are one and the same thing. We call this a legislative paradigm. As one scholar writes: “A law writing is more than a portrait of laws: it is law … Law written down becomes a source for legal practice … The magistrate’s task is no longer to discern justice, but to apply what the law writings prescribe for a certain kind of case.”

In the ANE, however, these two things were separate: “a conceptual separation exists between actual law and written law. That is, what is written may be a description of what law looks like, but what is written is not viewed as being ‘the law.’ ” Actual law—justice, order, righteousness—aren’t identical with written law; rather, written law points us in the direction of actual law—what we would call a non-legislative paradigm.

We see this play out in some of the other differences between law as we know it and law in the ANE. One of the main goals in the writing of our law codes today is comprehensiveness. The aim is to cover every aspect of life. Absolute comprehensiveness is obviously impossible—we can’t legislate right down to the details of every possible situation—but to help with that we have things like precedent to still retain some level of consistency. By contrast, “ANE legal collections … do not even try to be comprehensive; many important aspects of life and society are left unaddressed.”

Another way we can see this play out is the role legislation plays. In our modern legal system, “A chief goal is to ensure that legislators alone make the law and that judges, as far as possible, simply apply the law as it stands in the books.” But whereas written law serves as the basis for judging legal disputes in our society, in the ANE, written laws weren’t even considered—“In all the documents that we possess [from the ANE], no reference is made to any resource that is consulted in order to determine the judge’s ruling.” Deciding what the ruling would be was the job of the king, or whoever the king delegated those sorts of jobs to, according to what they believed would maintain order and uphold justice. Written law wasn’t there as legislation in the ANE. It was aspective: it laid out example rulings for a wide variety of cases—not so that those rulings would be carried out in such cases, but to give a sense of what shape justice and order are meant to take.

As such, law in the ANE isn’t legislation; it’s wisdom. Wisdom, in this context, is the intuition to be able to know justice, order, and righteousness when you see it. ANE legal collections didn’t give the verdicts for legal cases; it equipped those responsible to make wise judgments for themselves. As John Walton explains: “Wise living cannot be legislated. It is a matter of applying principles of wisdom, not of following rules.”

Torah as wisdom

How then should we read the Torah—the first five books of the OT, where we find all of its major legal collections? Well, since it was written in the ANE, we should probably read the legal collections in the Torah less like a modern law code, and more like other ANE legal collections. That doesn’t mean it’s the same in every respect—in fact there are some important differences between what we find in other ANE legal collections and the OT. But it does mean that when we read legal collections in the OT—especially a book like Deuteronomy, which in many ways is the pinnacle of OT law—we should approach it with the same categories that would have been used in the ANE. It means that when we read books like Deuteronomy we should read them less like legislation and more like wisdom.

“Torah”, usually translated “law” in our English Bibles, doesn’t actually mean law at all—at least not if what we mean by “law” is something like the way we use it today, along the lines of legislation. A better translation might be something like “guidance”, or “instruction”, or “teaching”—all words that are more along the lines of description than prescription. And, if this is the case (and I very much think it is), then, as one scholar has put it: “It may be reasonable to regard many Old Testament ‘laws’ as much more like wisdom literature than has been usual: they set up ideals to be aimed at by appearing to legislate.”

It doesn’t really come as a surprise, then, that “Scholars have long recognized the links between the book of Deuteronomy and biblical wisdom writings, especially the book of Proverbs.” Both have an emphasis on teaching and learning (Deut. 4:1; Prov. 1:2–6; 9:9). Both call their audiences to “hear”, or “listen” (שׁמע; Deut. 6:4; 9:1; Prov. 1:8; 2:10; 4:7). Both present the choice between the way of life or the way of death, and between blessing and curse (Deut 11:26–28; 30:19; Prov 1:29; 3:31–33), and both exhort their audience to choose life (Deut. 13:19; Prov. 4:10–13). They share many common themes. Both hold out life in the land—presumably the land of Israel, the Promised Land—as the fruit of being upright, or being cut off from the land for wickedness (Deut. 30:16–18; Prov. 2:20–22). Both have significant emphasis on the heart—Deuteronomy mentions the heart forty-five times; Proverbs mentions it fifty-three times. Both place significant emphasis on the “fear of Yahweh”—Proverbs 9:10 tells us that “The fear of Yahweh is the beginning of wisdom, and knowledge of the Holy One is understanding”; and Deuteronomy 10:12: “And now, O Israel, what does Yahweh your God ask of you but to fear Yahweh your God...?” We could go on, but I think the point is made: parallels between Proverbs and Deuteronomy abound.

What we’re not saying is that legal and wisdom literature are the same in every respect, such that we could merge the two into a single category. While there is a lot of overlap, they tend to approach things from different angles. The legal collections are for the sake of making judgments on disruptions to order in society, whereas the wisdom literature tends to “anticipate situations that will be faced and offer advice so that order will not be undermined, and in so doing they frame the values of society.”

Even so, Deuteronomy and Proverbs—law and wisdom—have the same goal in mind: to provide moral instruction for the sake of preserving order in society. And though they come at it from different angles, both seek to do so by promoting wisdom among the people of Israel, and by extension, to us. What all this means—and this is really what it comes down to—is that a large part of OT ethics (and, as we’ll see later, NT ethics too) is not about rule-keeping; it’s about wisdom.

We’re going to think more about what we mean by wisdom in a moment; but I just want to pause here, because some of you might be a little uncomfortable with this, and I would venture to guess that that has a lot to do with how you understand what wisdom is. One of the pitfalls I’ve often seen people fall into is to think of wisdom as morally neutral, like it’s just giving advice that you can take or leave. It’s as if we have things that the Bible says are fine; we have things the Bible tells us are wrong; then we have this grey area in the middle called “matters of wisdom”—areas we can agree to disagree. We have the boundaries set for us; where we are within the circle is up to us. Something we’re wanting to get across in this module is that more of life is morally charged than I think we initially realise. Saying that Torah is wisdom, not legislation, doesn’t empty it of any moral value—if anything, it increases its scope.

Wisdom and the good life

What we’ve seen so far is that OT ethics has a huge focus on wisdom. We saw that by flipping to the parts I think we’d be inclined to go to first to find out what the OT has to say about what “the good life” looks like, and thinking a bit about the context for those parts of the OT. And as we did so, we saw that its approach is much more like wisdom than it is a list of rules. Our next step, then, should be to spend some time thinking about what wisdom means, and how that shapes our lives so that we can live the good life.

There are a handful of books in the OT typically thought of as the “wisdom literature”—Job, Proverbs, and Ecclesiastes. It would be great to look at all three, but since it fits best with what we’re focusing on now, we’ll be spending the next little while just focusing on the book of Proverbs, really just taking a long, slow walk through the first seven verses.

1 The proverbs of Solomon son of David, king of Israel:

2 For learning what wisdom and discipline are;

for understanding insightful sayings;

3 for receiving wise instruction

in righteousness, justice, and integrity;

4 for teaching shrewdness to the inexperienced,

knowledge and discretion to a young man—

5 a wise man will listen and increase his learning,

and a discerning man will obtain guidance—

6 for understanding a proverb or a parable,

the words of the wise, and their riddles.

7 The fear of the Lord

is the beginning of knowledge;

fools despise wisdom and discipline (Prov. 1:1–7, HCSB).

Defining wisdom: the skill of living

The first thing we have to think about is what wisdom is: what do we mean by “wisdom”?

In Proverbs, the Hebrew word for wisdom is חָכְמָה. It carries with it the idea of skillfulness or ability. So, for instance, when the Israelites were building the tabernacle, God gave certain individuals חָכְמָה (Ex. 31:3)—the skill or ability necessary to perform the task at hand. חָכְמָה, in building the tabernacle, means skill and craftsmanship; it’s capability to perform the task at hand well. But whereas in Exodus it’s limited to building the tabernacle, in Proverbs, the scope of חָכְמָה is broadened to encompass all of life. One writer explains:

Wisdom is the skill of living. It is a practical knowledge that helps one know how to act and how to speak in different situations. Wisdom entails the ability to avoid problems, and the skill to handle them when they present themselves. Wisdom also includes the ability to interpret other people’s speech and writing in order to react correctly to what they are saying to us.

In short, wisdom is about living well.

It includes a perceptiveness about how the world works. Thomas Aquinas believed that wisdom is about understanding the most fundamental causes of things, and how that works itself out in the world around us. It comes with a recognition of the general cause and effect in the world, and an understanding of how we should structure our lives accordingly.

It’s a recognition that when we act a certain way, or when we do certain things, we can expect certain results. For instance: “Idle hands make one poor, but diligent hands bring riches” (Prov. 10:4); or, “A gentle answer turns away anger, but a harsh word stirs up wrath” (15:1); or, “A hot-tempered man stirs up conflict, but a man slow to anger calms strife” (15:18). We could spend hours fleshing out how each of those works out; but even just brushing past, we can see that there’s an intuitiveness to them—it’s how the world works, how it’s been wired. It’s part of the cause and effect of how things run: if you don’t put in the effort, you can’t expect the results; if you approach conflict with a level head, although in our anger it never feels like it’s going to work, often our words are more powerful, and go further in bringing some resolution. There’s a pattern and a rhythm to the universe, a set of norms, and wisdom is, in part, seeing what those are and living accordingly.

Now, perhaps that all sounds a bit overly optimistic—and in fact some scholars have been quite dismissive of Proverbs for that very reason: it’s nice when you describe this order to the universe that just works the way it should, but so often that just isn’t our experience. You don’t even need to leave the “wisdom literature” to get that: that’s the whole point of Job and Ecclesiastes—things don’t always go the way we hope they will. But I think that’s part of the point of those books: they wrestle with the fact that the world doesn’t always work the way that it should—but wisdom recognises that when it doesn’t, these are exceptions. It isn’t how things are meant to be, and wisdom is the perceptiveness to know how to handle those situations well, in line with how things should be—in line with God’s intended order for the world. One writer puts it this way: “Wisdom is concerned with the order in creation to help human beings acquire knowledge of their environment to achieve mastery over life.”

Wisdom, then, is knowledge, or understanding, or perceptiveness about how things tend to work, and how things are meant to work. But, as we’ve alluded to already, while wisdom includes knowledge and understanding, wisdom isn’t limited to knowledge and understanding. It begins with knowledge and understanding—we could say it presupposes knowledge and understanding—but in Proverbs, wisdom moves beyond mere knowledge and understanding. It is, as we saw already, practical knowledge. So, as one scholar writes: “A person could memorise the book of Proverbs and still lack wisdom if it did not affect his heart, which informs behaviour. Ḥokmâ in Proverbs does not refer to the Greek conception of wisdom as philosophical theory or rhetorical sophistry.” Rather, it’s the skill to handle what life throws at you to respond appropriately.

Wisdom is the starting point; coupled with wisdom there in v. 2 is its outworking: “discipline”, or “instruction”, as some translations have it. Discipline is the setting aside of comfort or pleasure for the sake of some further good. That could mean self-discipline. We might think of training or practicing for something. It’s when you go for that first run in the beginning of January because it’s never worked before but this time you will stick to your New Year’s Resolutions and get back in shape. So you go for that first run all ambitious and excited and you get back in pain, and sweating, and wondering why you’re doing this to yourself—but though it’s uncomfortable now, you see the goal: there’s good on the other side of this.

Or we might think of discipline in another sense: in terms of punishment, which has as its goal education and correction. So when we say that discipline is the setting aside of some comfort or pleasure, that can include somebody else setting it aside for you—you might not have a say in the matter, and, given the choice, you might decline. But the goal of discipline is for your good. The principle still stands, though, that discipline isn’t a once-off thing. Discipline in this sense may be once-off (maybe more, depending on how quickly you learn), but it’s course correction; when you start veering off to the left or to the right, it’s knocking you back on track.

I think both senses are there in v. 2. The Hebrew word here for discipline is מוּסָר, and it comes with connotations of an instructor–student relationship, where the instructor—whether that’s the parent, teacher, perhaps even God, or life experience—gives correction, and always for the sake of education; “it thus entails shaping character.”

Proverbs isn’t just interested in how we act, but how we are. It isn’t just interested in our behaviour, but in the source of that behaviour: the heart. So we read in Proverbs 4:23: “Above all else, guard your heart, for everything you do flows from it.” We aren’t just called to act wisely, but to be wise. “Instruct a wise man, and he will be wiser still; teach a righteous man, and he will learn more” (9:9).

Character doesn’t just happen, though. Character is what is shaped over time—“the proverbs don’t simply lead to a change of behaviour but encourage attitudes and behaviours that over time become habits and contribute to the transformation of character.”

Proverbs starts with wisdom and discipline, and in those first few verses we see a number of other virtues associated with wisdom: discipline; understanding; wise instruction; righteousness, justice, and integrity; shrewdness; discretion; guidance. “Wisdom in the summary statement of the book’s purpose (1:2) entails all the other virtues listed in the preamble.”

One more thing we should notice about wisdom is that it’s inherently ethical in nature. Wisdom in Proverbs is a moral category. Look at v. 3: wisdom is for “receiving prudent instruction in righteousness, justice, and integrity.” One writer explains: “These are ethical terms, and as we read on we will see that one cannot possess them without wisdom—nor wisdom without righteousness, justice and virtue. In other words, wisdom in Proverbs is an ethical quality. The wise are on the side of the good.”

We find it put in parallel with other moral terms: “I am teaching you the way of wisdom; I am guiding you on straight paths” (Prov. 4:11). We’re meant to picture a father teaching wisdom to his son. And notice what he says further down in the same speech: “The path of the righteous is like the light of dawn, shining brighter and brighter until midday. But the way of the wicked is like the darkest gloom; they don’t know what makes them stumble” (vv. 18–19).

Straight after the prologue in ch. 1, we read of the son—the one sitting under the teaching of wisdom, the one in the story we should identify with—invited to participate in evil (1:8–19). He, and we, are exhorted rather to pursue wisdom:

9 Then you will understand righteousness, justice,

and integrity—every good path.

10 For wisdom will enter your mind,

and knowledge will delight your heart.

11 Discretion will watch over you,

and understanding will guard you,

12 rescuing you from the way of evil—

from the one who says perverse things,

13 from those who abandon the right paths

to walk in ways of darkness,

14 from those who enjoy doing evil

and celebrate perversion,

15 whose paths are crooked,

and whose ways are devious (Prov. 2:9–15).

Throughout Proverbs we see wisdom contrasted with other moral categories like wickedness and folly, quite often presenting two paths: the way of wisdom, and the way of folly, often personified as two women; the way of righteousness, and the way of wickedness. “One cannot be wise without being righteous. In the same way, folly and wickedness are inextricably intertwined. Foolish behaviour is evil.”

To come back to something we said earlier, this isn’t the way we tend to think about wisdom. The way I usually hear wisdom explained is as this morally neutral category somewhere in the middle—we have what’s clearly right, what’s clearly wrong, but a lot of life is lived in the middle, in this morally neutral zone, where we’re kind of free to just do what we want. Wisdom is doing that skillfully, in that it’s the sort of trait you want to be successful as you move around that middle bit. But it’s treated more like good advice than something that’s morally binding. It’s seen more as a take-it-or-leave-it sort of thing.

What Proverbs shows us is that all of life is morally significant. To come back to what we were saying about wisdom and law, while they have their differences, wisdom and law are the same in that they’re morally binding.

Wisdom is a moral category. To come back to what we said earlier, this is a major point we should see about the good life: thinking about ethics through the lens of wisdom doesn’t empty it of moral value; if anything it increases its scope. More of life is morally charged than we initially realise.

What that means is that wisdom isn’t a nice-to-have; it’s essential. Proverbs 4:7: “The beginning of wisdom is this: Get wisdom. Though it cost all you have, get understanding.” One scholar puts it this way: “For the authors or editors of the book this acquisition of wisdom is not an option to be taken up or discarded at whim; it is essential to the good life.” Wisdom is everything. We don’t always see it that way, but wisdom is central to the good life. It pervades every part of our lives, and attaches moral weight to every decision we make.

But we don’t always see it that way. And here’s an example that I find usually makes my point: how many of us procrastinate? How many of us are okay with our procrastination? Now, to be clear, by “okay with”, I mean that unless you’re actively working against your tendency to procrastinate, unless you’re making a conscious effort and putting steps in place, you’re okay with your procrastination. My experience is that many people aren’t just okay with their procrastination; they boast about it.

Is procrastination a sin? Yes. It’s laziness. And Proverbs consistently calls out the lazy. “One who is slack in his work is brother to one who destroys” (18:9); “The slacker does not plow during planting season; at harvest time he looks, and there is nothing” (20:4); “Don’t love sleep, or you will become poor; open your eyes, and you’ll have enough to eat” (20:13). Laziness is unwise. But when we realise that wisdom is a moral category, it follows that things like laziness and procrastination are moral issues.

Grounding wisdom: the fear of Yahweh

We’ve said that the basis of OT ethics is maintaining order. That’s what the legal collections are there for; that’s what the wisdom literature is there for. It’s important for understanding OT ethics. But it isn’t the whole story. The good life in the OT isn’t just based on order in society; it’s based in the fear of Yahweh. Proverbs 9:10: “The fear of Yahweh is the beginning of wisdom, and knowledge of the Holy One is understanding.”

In a previous module we spent some time thinking together about what that phrase “fear of the Lord” means, so we’re not going to spend too much time on it now. But I do want to say two things.

The first is that the fear of Yahweh has to do with our posture before him. It’s the attitude with which we approach him, standing in awe of the one who made the heavens and the earth. As one writer puts it: “Fear puts one in the proper attitude (humility) to receive instruction that ultimately comes from God, though perhaps mediated by his human agents.”

The second thing is that much of the wisdom in Proverbs is observational wisdom—it can be seen in the world around us. Proverbs 25:17 says: “Seldom set foot in your neighbor’s house; otherwise, he’ll get sick of you and hate you.” You don’t have to believe in God to appreciate that that’s the truest thing you’ve ever heard. But we’ve also seen that wisdom is a perceptiveness about the cause and effect of the world around us, and living well in light of that. True wisdom must take into account all of just reality—not just the order we see, but the One who orders it. True wisdom is found not merely in living a certain way, but in relationship with Yahweh.

The good life in the New Testament

We’ve spent the past while thinking together about wisdom. And we’ve been doing that because what we’ve been saying is that the good life in the OT looks less like rule-keeping, and more like wisdom. We’ve seen that in the wisdom literature (mainly Proverbs); but we also saw that in the legal collections in the OT (viz. the Torah). Although there are important differences between law and wisdom literature in the Bible, we shouldn’t put a hard divide between them, because when we read OT law in its historical context, what we find is that the legal collections should be read less like legislation and more like wisdom.

But as time went on, things changed.

Remember what we saw earlier: the difference between legislative and non-legislative paradigms. Part of the evidence for them using a non-legislative paradigm can be found in Aristotle:

[In those lands] laws enunciate only general principles but do not give directions for dealing with circumstances as they arise; so that in an art of any kind it is foolish to govern procedure by written rules …; it is clear therefore that [in those lands] government according to written rules, that is laws, is not [deemed] best, for the same reason.

Why would Aristotle talk about those nations who don’t judge cases by written law? Because “these ones” do—it was the Greeks who made the significant move over from the non-legislative to the legislative approach. Toward the end of the fifth century BC, things changed. Written law took up a new position as a presentation of actual law, not just something that pointed to it. One scholar summarises the process:

Ancestral legal traditions were harmonised, and a single consistent code was produced and written on the walls of the royal stoa. New laws, drafted by a board of legislators, were deemed superior to the laws of the assembly, and unwritten custom was stripped of legal force so that courts and magistrates had to follow and enforce only written laws. … Athens established not merely the rule of law, but the rule of written law—law writings as the source of law.

Now, Aristotle has things to say to that; according to Aristotle, the judge who only ever appeals to written law to the expense of justice is deficient. But we’ll think more about that next week. But already I’m sure you can think of ways that this paradigm shift shows itself in the NT.

Take Mark 7, for instance: Jesus is challenged by the Pharisees because his disciples don’t wash their hands before eating. Jesus’ response is effectively that they’re so worried about outward cleanness and rule-observance that they’re missing the point of the law entirely. They’re so focused on their rule-keeping that they can be so pedantic about some things, while getting away on a technicality on others. Jesus’ response is that God isn’t interested in that; he’s interested in what’s going on in their hearts: “What comes out of a person is what defiles them. For it is from within, out of a person’s heart, that evil thoughts come—sexual immorality, theft, murder, [and so on]. All these evils come from inside and defile a person” (vv. 20–23).

We also see that in the Sermon on the Mount. It says in the law: “You shall not murder.” But Jesus pushes past what it says to what it’s pointing to: harboring feelings of resentment and hatred (Matt. 5:21–24). It says in the law: “You shall not commit adultery.” But Jesus pushes past that and condemns the lust that it all begins with, and upholds the sanctity of marriage (Matt. 5:27–32). Jesus isn’t interested in outward actions; he’s interested in the intentions of the heart. Craig Keener explains that when Jesus says in Matthew 5:17: “I haven’t come to abolish the the law,” he was opposing “not the law but an illegitimate traditional interpretation of it that stressed regulations more than character.”

Like we saw with the OT, what we’re looking for isn’t a list of rules—which I think is often how we tend to read the NT: as a revised list to make up for the weirdness of the laws we find in the OT. In the NT, as in the OT, God isn’t interested in rule-keeping, but character. God isn’t interested in a renewed enthusiasm (as if just trying harder were the answer), but a renewed mind and heart.

But there is a difference that comes with the NT—a difference that’s there in the Sermon on the Mount. In the Sermon on the Mount Jesus is teaching his disciples (Matt. 5:1–2)—though in the hearing of all the crowds (5:1; 7:28–29)—about the kingdom of heaven. Jesus is setting forth what it looks like to be a citizen of God’s kingdom—what it looks like to be a part of the kingdom he has come to establish. N. T. Wright puts it this way: “God’s future is arriving in the present, in the person and work of Jesus, and you can practice, right now, the habits of life which will find their goal in that coming future.”

This is something we thought about in our module on biblical theology, so we’re not going to go into detail now. What we will say is that, though the kingdom of heaven has come in Jesus, and though it has broken in through his life, death, resurrection, and ascension, it hasn’t been fully realised—that will only come when Jesus returns, when everything will be made new. But the age of the Spirit has begun. The Holy Spirit has been poured out on all who call upon the name of the Lord (Acts 2).

That’s what N. T. Wright is getting at: because the age of the Spirit has begun, and because we have the empowering presence of the Holy Spirit with us now to enable us to live as citizens of the world to come, we should do so. That’s what Paul is getting at in Galatians 5 when he talks about walking by the Spirit, and keeping in step with the Spirit.

That’s also what Paul means when he talks about the “fruit of the Spirit” (vv. 22–23). It’s really a powerful metaphor. Leanne and I were growing tomatoes for a while two years ago. It was one of those Checkers plants, and for a while it grew really well. (I think we only ended up getting like four tiny little tomatoes from it, but that doesn’t help my point, so we’ll just ignore that bit.) The plant just grows. The forces of nature at work in its growing weren’t something Leanne or I could control: it just happened. But that doesn’t mean we could just leave it. We still had a part to play. We had to water it. We had to make sure it was getting the sun it needed. We had to move it around a few times, because our rats seemed to enjoy digging it up. That’s how it works in cultivating the fruit of the Spirit. We need the Spirit’s empowering presence—we can’t make these virtues grow in our lives by ourselves. But we also can’t sit back and wait for the magic to happen. It takes effort—consistent effort. It takes hard work and doing the same things over and over again.

But notice also what Paul says: the fruit of the Spirit—not fruits (plural). Love is front and centre. There’s a reason for that—in 5:14 Paul says that the whole law is fulfilled in the command to love. But it’s fruit: singular. N. T. Wright explains:

Just as Plato and others insisted that if you want truly to possess one of the cardinal virtues you must possess them all—because each is, as it were, kept in place by the others—so Paul does not envisage that someone might cultivate one or two of these characteristics and reckon that she had enough of an orchard to be going on with. No: when the Spirit is at work, you will see all nine varieties of this fruit. Paul does not envisage specialization.

Conclusion

We’ve spent some time thinking about what the good life looks like from a biblical perspective. Really that has meant three things. The first was the shift from thinking about morality in terms of rules to thinking about it in terms of wisdom. We saw that wisdom is a moral category, and that much more of life is morally charged than we may have realised.

Which brings us to the second thing: the good life in the Bible is more focused on character than actions. Our actions matter. But our actions don’t matter nearly as much as where our actions flow from: our hearts. We saw this way of thinking pervaded the book of Proverbs, and that this way of thinking flowed through to the NT.

And as we get into the NT we thought together about the third thing: that the good life isn’t just about the now, but also the not yet. The age of the Spirit has begun. It’s an age that will only be fully realised when Christ returns, but it’s an age that has broken into the now. The good life for the Christian is not just a good life for the now, but a life lived by the Spirit, bearing the fruit of the Spirit, struggling against the flesh, awaiting the day when it will give way to everlasting joy in the presence of God.