Friendship

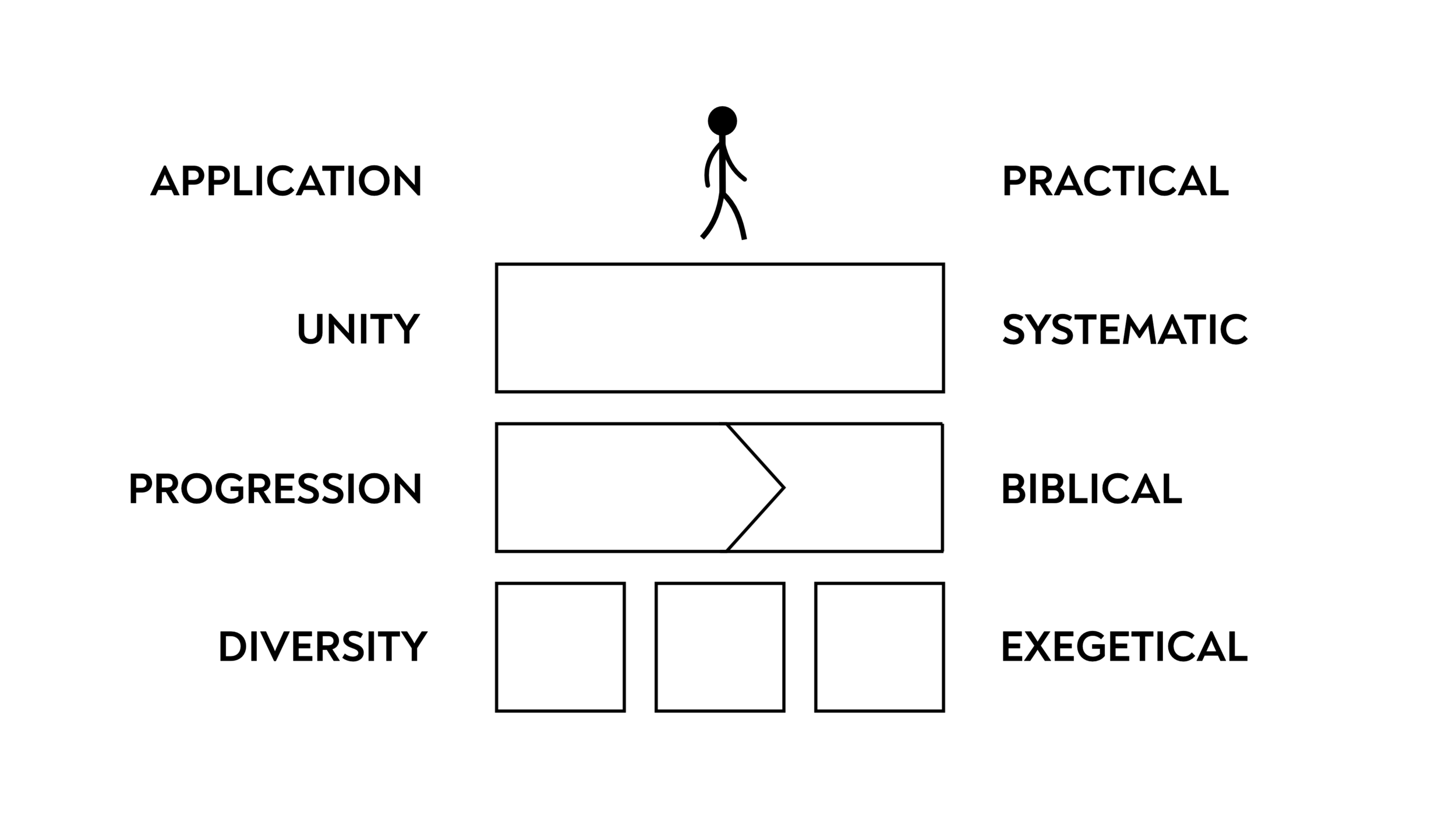

We’re busy looking at practical theology in this module, with a focus on ethics. Even though these days we tend to think about ethics in terms of rule-following, we saw in the first week that scripture gives a special place to wisdom and character, and we saw last week how philosophy can be used to fill in some of the details of that picture with virtue. In this lesson we’re going to apply some of what we’ve learned to the topic of friendship.

Now, it may surprise some of us that we’re spending an entire lesson on friendship—it doesn’t sound like an obvious first choice for a topic in a module on ethics. But when you shift your thinking from rules to wisdom and from actions to character, then friendship takes on a special significance in how we think about the good life. We’ve said that living the good life requires that we develop our character, that developing character requires that we cultivate virtue, and that we cultivate virtue more in our small daily choices that we do in the rare big decisions of life. While our friends may not always be there when we need to make difficult decisions, they are certainly there in our daily interactions—influencing how we think, what we value, and how we reflect on what happens to us. Thus Paul warns us that, “bad company ruins good morals.” (1 Cor 15:33) Proverbs warns us to:

Make no friendship with a man given to anger, nor go with a wrathful man, lest you learn his ways and entangle yourself in a snare. (Prov 22:24–25)

Confucius, the ancient Chinese philosopher, tells us that “Virtue is never solitary; it always has neighbors.” (Analects 4.25) In Aristotle’s Nichomachean Ethics, two out of the ten books are on the question of friendship. And a commonly-repeated idea these days is that you’re the average of the five people you spend the most time with, which applies not only to the kinds of movies you like or the sorts of conversations you have, but also the values you hold and the character you develop. So, then, it’s worth spending some time thinking about friendship from an ethical perspective.

What is a friend?

The first thing we should get clear on is what it means to be a friend. The Bible doesn’t have a central place where it defines friendship for us—the closest thing to a definition I’ve managed to find comes in Deuteronomy, where Moses is warning Israel against turning to other gods. He says that they should not turn to other gods even if someone close to them encourages them to, and in doing so lists some people that they might be close to:

If your brother, the son of your mother, or your son or your daughter or the wife you embrace or your friend who is as your own soul entices you secretly, saying, “Let us go and serve other gods”... you shall not yield to him or listen to him... (Deut 13:6, 8)

We can draw two things from this passage to help us put together a biblical definition of friendship.

First, the friend is the only non-family member listed here. When they function well, our families are the closest people to us: they’ve seen us at our best and our worst and love us anyway. Our friends, then, are the next closest thing we have to this in the absence of blood relation. In fact, a few times in Proverbs a friend is directly compared to a brother:

A friend loves at all times, and a relative is born to help in adversity. (Prov 17:17, NET)

Don’t abandon your friend or your father’s friend, and don’t go to your brother’s house in your time of calamity; better a neighbor nearby than a brother far away. (Prov 27:10)

The second thing to note about this passage is that it describes a close friend as “one who is as your own soul”. When trying to unpack what this means, we might guess that it means something like “love your friend as you love yourself”. But, while it’s certainly right that you should love your friends, you’re also supposed to love your neighbor as yourself. In Israel, this would have included anyone living within the borders of the nation, and Jesus extends it even further with the parable of the Good Samaritan.

Perhaps this is why a close friend is described specifically as one who is as your own soul, rather than the more generic description of someone you love. The difference between a friend and a neighbor, then, is that the connection you have with your friend is somewhere between the unique connection you have with your own self and the general connection you have with any of your neighbors. Just as your family is said to be your own flesh and blood, and as your spouse is said to be one body with you, so your close friends are said to be as your own soul.

Aristotle actually says something similar when he talks about friendship (NE IX.4). He concludes that a friend should be thought of as “another self”, based on the ways we typically think friends should treat one another (NE IX.4):

Friends wish and do good for one another

Friends wish that each of them exists

Friends share their lives with each other

Friends share some or many of their tastes with one another

Friends grieve and rejoice with one another

Each of these, Aristotle says, is something we should be doing for ourselves if we’re treating ourselves right, and so it follows that we treat our friends as if they were another self.

He also has another way of thinking about friends that can also be quite helpful. He notes that we love our friends, and that generally speaking there are three reasons we would love something: (1) because it is useful to us, (2) because it is pleasant to us, or (3) because we find it desirable for its own sake. I love my car because it’s useful for getting me around, I love wine because it’s pleasant to drink, and I love my fiancée for her own sake.

Of course, even though I love cars and bottles of wine, they are not my friends. This is because the love is not mutual: I love my car and the wine, but they don’t love me back. A friendship requires that both friends know that they’re in a friendship, and love each other accordingly.

A utility-friendship is one in which two people spend time together primarily because one is useful to the other in some way, such as between a nurse and a patient, or between someone and their personal trainer at the gym, or between someone and the local laundromat where they get their clothes washed. These examples illustrate that a utility-friendship doesn’t have to be a negative thing—in fact, once it becomes negative it’s not really a “friendship” at all, it’s just manipulation or extortion.

A pleasure-friendship is one in which two people spend time together primarily because they bring each other pleasure in some way, such as your running partner, or a weekly gaming group, or people that you regularly go to nightclubs with but who you don’t spend much time with otherwise.

In both a utility-friendship and a pleasure-friendship, we are friends with people primarily for what we can get out of the friendship for ourselves. By contrast, in a virtue-friendship we are friends with someone because we desire them for their own sake. This isn’t to say virtue-friendships aren’t pleasant and useful. They are pleasant and useful, but the focus is on the other person more than it is on what we can get out of our friendship with them. Virtue-friendship is the truest form of friendship and in some sense the most stable, since it doesn’t only depend upon you being useful to someone or them being pleasant to you.

So these are the definitions of friendship we have. Scripture and Aristotle agree that a friend—or at least a close friend—is someone who we consider another self, one who is as our own soul. Aristotle notes that there are three senses in which this might be true, based on the way we love our friends. Of these three, it is the virtue-friendship that can be most truly described as loving another as our own soul.

What makes a good friend?

Now that we know what a friend is we can ask what makes someone a good friend. This is relevant both from the perspective of trying to be a good friend to others, as well as making sure we are looking for the right things in our friends. According to biblical ethics, there are three marks of a good friend, which we’ll go through in turn: (1) they’re there for us in difficult times, (2) they help us become better people, and (3) they make life better and more pleasant.

Good friends help us in tough times

Biblical wisdom recognizes over and over again that life is hard—it’s full of bad fortune, difficulties, and adversity. This is sometimes because people sin against us, but often it’s just the result of certain incongruities that exist in God’s world. In Ecclesiastes, the Teacher describes this well when he says:

Again I saw that under the sun the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, nor bread to the wise, nor riches to the intelligent, nor favor to those with knowledge, but time and chance happen to them all. For man does not know his time. Like fish that are taken in an evil net, and like birds that are caught in a snare, so the children of man are snared at an evil time, when it suddenly falls upon them. (Eccl 9:11–12)

Earlier in Ecclesiastes, the Teacher makes the point that facing these difficulties is easier if we have others in our life:

Two are better than one, because they have a good reward for their toil. For if they fall, one will lift up his fellow. But woe to him who is alone when he falls and has not another to lift him up! Again, if two lie together, they keep warm, but how can one keep warm alone? And though a man might prevail against one who is alone, two will withstand him—a threefold cord is not quickly broken. (Eccl 4:9–12)

When applying this to friendship, our friends are meant to be those who, like our family, are people we can rely on in difficult times. We shouldn’t have to worry about them abandoning us because we are as their own soul: just as it would pain them to go through a difficulty, so too are they pained when they see us going through one. Thus, as we saw earlier, Proverbs agrees with Ecclesiastes in the value of friends during hard times:

A friend loves at all times, and a relative is born to help in adversity. (Prov 17:17, NET)

Don’t abandon your friend or your father’s friend, and don’t go to your brother’s house in your time of calamity; better a neighbor nearby than a brother far away. (Prov 27:10)

In terms of the three types of friendship that Aristotle outlined, this principle fully applies to virtue-friendship, but applies only in a qualified way to utility- and pleasure-friendship.

In the case of utility-friendship, the friends might help each other to maintain the relationship of the one being useful to the other, but would give up when this becomes too much of a burden. For instance, if your trainer at the gym is not able to come to work because of personal reasons you may wait a bit in the hopes that they come back or do something to help their situation, but eventually you’ll start looking for another personal trainer. Likewise, if your running partner stops coming you might try to help them, but you also might start looking for another partner without giving it much thought. In each of these cases, this happens because the friendship only applies to a small slice of life and is based on something that can be replaced very easily. We are as one soul with our personal trainer only insofar as we both go to the gym, and we are as one soul with our running partner only insofar as we both go running every morning.

By contrast, virtue-friendship is not limited to one part of life or one aspect of a relationship, but is between two people each with complete lives. Thus, when we experience pain or difficulty in any part of our lives, our virtue-friends will share in that pain and seek to help us whenever they can. And because the friendship is based on the people themselves rather than what they can give each other, there is far less risk of abandonment.

Unfortunately, it doesn’t always work this way. Hopefully, not many of us would have experienced this, but it does happen that people who we think of as our virtue-friends abandon us when life gets tough, or are not there when we need them the most. Using poverty as an example, Proverbs says:

Wealth attracts many friends, but a poor man is separated from his friend. (Prov 19:4)

Why does this happen? Why do people we thought were our virtue-friends abandon us? The most obvious answer is that they’re just a bad friend, or have some failing in their character. There’s not much we can do in this case. We can talk to them about it or we can learn to not rely on them in future, but this is easier said than done when we’re currently going through a difficult time.

Another reason why a friend might not be there when we’re relying on them, is that there’s an asymmetry in the way we think about the friendship: one of us thinks we’re in a utility- or pleasure-friendship while the other thinks we’re in a virtue-friendship, or perhaps both of us think we’re in a virtue-friendship but we’re differently committed to it. In this case, the asymmetry leads to us thinking they’ve abandoned us, but in fact, it’s just a misunderstanding of what each person has invested into the relationship. Of course, this is no consolation when we’re busy going through a hard time, so it’s worth evaluating the kinds of friendships we have before their behavior forces us to so when it’s too late. In this proverb, the friends who are attracted by wealth or repelled by poverty should not be mistaken for virtue-friends, no matter how useful or pleasant they are to us.

Finally, and most complicated, a friend might not be there for us not because they don’t want to be, but because it’s inappropriate for some reason. You’ll recall last week that we discussed the doctrine of the mean, which says that every moral virtue is in the middle between a vice of excess and vice of deficiency. What’s appropriate is determined on a case-by-case basis, but it typically includes consideration both of what the person needs and how much we’re able to help. To use a concrete example, imagine a friend of ours is having a hard time with one of their colleagues. In this case, being there for them means being a sounding board and perhaps giving them advice. But what if at the moment you don’t have time to spare because you are going through a more serious issue in your life? Is it a fault of yours that you can’t spare time for your friend right now, or to listen to them? I presume many of us would say no, and I think that’s right. Just as it’s not your fault if you can’t give you money that you don’t have, so too it’s not your fault if you can’t give time you don’t have.

Alternatively, let’s assume you do have time but that this is the eighth or ninth time your friend is coming to you with this same problem. You’ve already listened to them at length and given them advice, but they’ve ignored you and continue to complain to you about all of this. At this point, you may rightly start wondering what your friend really needs. Are they using your conversations as a way to fester their anger or feed their resentment? Are they just enjoying complaining? If you suspect that they are, then even if you have time to spare it might not be best to do. It might be worth talking to them about it, and not enabling them. To them, this may all come across as if you’re abandoning them, and they might even criticize you for it; but in fact, you’re looking out for their best interests.

These are all things we need to keep in mind when it comes to friendship and hardship. A burden is something we can share with our good friends, and often the blessing that friends bring will mean we have less of a burden to share. Sometimes they will let us down and sometimes that will be because they are bad friends, but not always.

On the flip side, we should seek to be people who are willing to bear the burdens of our friends, at least when that’s the best thing for them. And of course, when it comes to our inspiration for this we need look no further than Jesus, who humbled himself to become a man, that he might die for us and make it possible for us to share in God’s plans for the world:

This is my commandment, that you love one another as I have loved you. Greater love has no one than this, that someone lay down his life for his friends. You are my friends if you do what I command you. No longer do I call you servants, for the servant does not know what his master is doing; but I have called you friends, for all that I have heard from my Father I have made known to you. (John 15:12–15)

Good friends help us become better people

The next feature of a good friend is that they help their friends become better people. As it says in Proverbs:

As iron sharpens iron, so a person sharpens his friend. (Prov 27:17, NET)

Whoever walks with the wise becomes wise, but the companion of fools will suffer harm. (13:20)

And as Master Zeng says in the Analects of Confucius:

The gentleman acquires friends by means of cultural refinement, and then relies on his friends for support in becoming good. (Analects 12.24)

We’ve said that the good life is achieved by growing in wisdom and developing character, that character is developed by cultivating virtue, and that cultivating virtue requires daily practice. We said that the signs that you’ve acquired a virtue are (1) that you find it easier to reliably perform good actions for the right reasons, and (2) that you take pleasure in doing so. But before we’ve actually cultivated a virtue, this means we’ll likely struggle with two things: first, we’ll struggle to figure what the right thing to do is, and second, we’ll struggle to bring ourselves to do it. Good friends can help us with both of these, and in doing so they can help us become better people. And likewise, we have the opportunity to help our friends become better people.

Because they share their lives together, friends have the opportunity to discuss the decisions they face, both big and small. When one of them is trying to figure out what would be too much or too little in a case of generosity, or whether they should face up to a particular threat rather than leave it alone, or whether their patience is being taken advantage of, or any other question relating to how they should act, they can look to their friends for an outsider’s perspective. Sometimes, even when we know the right questions to ask, we struggle with the answer because we’re too invested in the outcomes. In times like these, friends can encourage our good tendencies and act as a counter-balance to our bad ones.

On the other hand, friends can also be a bad influence on us, if they encourage our bad tendencies and act as counter-balance to our good ones. Thus, Proverbs says we should be careful about who we spend time with:

Make no friendship with a man given to anger, nor go with a wrathful man, lest you learn his ways and entangle yourself in a snare. (Prov 22:24–25)

One who rebukes a person will later find more favor than one who flatters with his tongue. (Prov 28:23)

Now, in a way, just as friendship is mutual love, helping friends reflect on their life can be mutually beneficial. In our early years, our lives are quite similar to our friends, but as we get older our lives tend to get more varied—people start different jobs, get married at different times, struggle with different losses, and so on. In helping our friends think through the situations in their lives we share to some extent in their experiences and choices before we’re faced with similar experiences and choices in our own lives. Or perhaps we might never have had to think about them were it not for our friend, and in helping them become generous or kind or courageous we grow indirectly in these things as well.

So good friends help one another become better people by helping each other to reflect on their actions, to ask the right questions and arrive at the right answers. But they also help one another when they know the right thing to do but find it difficult to do. This has to do with the idea called “ethical continence”. Unlike how we use the word today ethical continence has nothing to do with your bladder, but is about your ability to act in accordance with what you know is right.

We can draw a spectrum, where on the one end we have the virtuous person who knows the right thing and is able to do it with ease, and on the other side, we have the vicious person who does not know what is right and does bad things with ease. Then in the middle, we have these two states, continence and incontinence. The continent person knows the right thing to do but has to force themselves to do it—their mind is pointing them in the right direction, but because they find it so unpleasant, they struggle to bring themselves to follow through. They can do it, but it’s hard. Think of a case when you know you need to have a difficult conversation with someone, but you really don’t want to. You might put it off until you have to talk to them, or you might have to just force yourself to start the conversation despite all the excuses you put in your way. The incontinent person is in an even worse place: they know the right thing to do but just cannot bring themselves to do it. This would be the case where the prospect of having that difficult conversation just cripples you, and you can’t bring yourself to broach the topic no matter what you do.

Virtue and vice are stable because they reinforce themselves by making action easy and pleasant. By contrast, continence and incontinence are unstable, because they make the person divided against themselves. The continent person has the hope of becoming virtuous if they win enough battles with themselves; over time, they will see that the right course is more often the best course, and so they will gradually chip away at their internal resistance to it and start taking pleasure in it. On the other hand, the incontinent person runs the major risk of becoming vicious; it’s draining, constantly knowing you’re not doing what you should, and so over time you will be tempted to justify your behavior and thereby delude yourself into believing that bad things are not actually so bad after all.

I’m sure many of us can relate to all of this—we’ve been in situations where we know what we’re supposed to do but just can’t bring ourselves to do it. And this is where our friends can help us. They can be an external source of encouragement for good action; they can hold us back when we’re inclined to act rashly; they can rebuke us when we’ve given in to our temptations; and they can help us see the good or bad in a particular situation. With their help, we can move along the spectrum from incontinence to virtue—although perhaps it would be more accurate to say that they can drag us from incontinence to continence, and then help us move from continence to virtue. Ultimately, as we become gradually better, we will become more mature and less dependent on outside help.

Now, it’s not like we need to be perfect before we can help our friends like this—it helps if we already have acquired a virtue when helping someone more towards it, but it’s not a strict requirement. Remember, every moral virtue lies in the middle between two vices, one of excess and one of deficiency. If I’m more inclined towards the vice of excess and my friend is more inclined towards the vice of deficiency, then we can pull each other towards the virtue in the middle. Or if we’re both inclined towards the same vice, then we can at least be accountability partners for one another—although this could lead the two of us to justify our actions when we see each other act in accordance with vice.

Of course, friends can only help one another become better people if they’re open with one another and concerned with developing character. If the way we share our lives looks more like a pleasure-friendship, then we should not be surprised that we are not helping each other grow, or perhaps even hindering each other from improving. If instead we consider virtue important, including the virtue of our friends, then we’ll be on the right track.

Good friends make life better

All of this may make virtue-friendship sound a bit of like a chore. But as we said in the beginning, while virtue-friendship is pleasant and useful, it’s also more than these things. It’s friendship for the sake of another, which like the good life is both difficult to attain but worth it in the end. There’s a proverb that suggests something like this:

Oil and perfume make the heart glad, and the sweetness of a friend comes from his earnest counsel. (Prov 27:9)

The earnest council of friends can sometimes be a difficult thing to hear, but it will be very beneficial to us in the long run.

This brings me to the last thing we need to say about good friends. So far we’ve said that they support one another in tough times and help one another become better people, but if this were all there was to being a friend then the person who is both fortunate and virtuous would have no need for friends. “But it seems strange,” says Aristotle,

… when one assigns all good things to the happy man, not to assign friends, who are thought the greatest of external goods. (NE IX.9 1169b5–10)

Recall that in the previous lesson we said that true happiness depends to some extent on material goods, but that it ultimately has to do with cultivating virtue. Thus, the happiest people would be the least impacted by tough times and the least in need of becoming better, and so from what we’ve said they’d be the least in need of friends. But they should still have friends, because the third feature of good friends is that they make life better and more pleasant. We can see this in three ways.

First, the more we live the good life the more we take pleasure in virtuous things. Now, we should take pleasure in our own virtuous actions, but we can also take pleasure in the virtuous actions of our friends or the virtuous actions we do with our friends. We might take pleasure in bringing our lives to God in prayer, and all the more in doing so with our friends. We might enjoy generosity, and we take joy in our friends when we hear about the generous things they do. We might love bravery, and be inspired by the courage of friends when they make difficult decisions. Thus, friends make life more pleasant, even for the happy person.

Second, good friends give us opportunities to practice virtue. A good friend will be easier to forgive, to be generous to, to pray with, to reflect on life with, to honor, and all sorts of other good things that we should do for all people, but which we need to practice in if we are to maintain virtue.

And finally, we can see that even happy people need friends by considering the three types of friendship outlined by Aristotle. We said that while utility- and pleasure-friendships are entered into for our sake, in virtue-friendship we love our friend for their own sake. Thus it shouldn’t matter if they cannot be useful in helping us in hard times or with becoming better, since the primary goal is in sharing our lives with them because we find them desirable in themselves.

So, Aristotle says, “the presence of friends, then, seems desirable in all circumstances” (NE IX.11 1171b25ff); Confucius says, “virtue is never solitary; it always has neighbors.” (Analects 4.25); the Teacher in Ecclesiastes says, “Two are better than one” (4:9); and Solomon says in the Proverbs, “A friend loves at all times” (17:17).

Various questions about friendship

Now that we have an idea of what a friend is as well as what makes someone a good friend, we can try and answer some questions about friendship.

Do Christians make better friends?

The first question is whether being a Christian makes you a better friend. In the case of pleasure- or utility-friendships, there seems to be no reason to think so, unless the pleasure or utility is uniquely Christian (for example, the friendship between the members of a weekly prayer group, or between a parent and the Sunday school teacher of their children). When asking this question, we primarily have virtue-friendships in mind. Do Christians make better virtue-friends?

On the one hand, obviously not. Like all humans, Christians are sinful and prone to fail others because of weakness or selfishness. There is also no guarantee that we will be more virtuous than our non-Christian counterparts—we have the Holy Spirit to help us grow in virtue, but experience and scripture show us that that is by no means a guarantee that we’ll cooperate with his work in our lives.

On the other hand, there are two respects in which good Christians can make better friends. First, we’ve said that good friends help us become better, and do so by helping us cultivate virtue. Good Christians can help us develop all the virtues, including the theological ones, whereas good non-Christians will only help us develop the moral and intellectual virtues. Second, Christians can understand better the unique struggles and experiences we have as Christians in this world, and so are to some extent more likely to help us reflect properly on how to respond to them.

Now, this doesn’t imply that we should only have Christan friends. It is quite likely that none of our friends, whether they be Christian or non-Christian, are completely virtuous. It’s likely that the non-Christians in our lives will be best in helping us with some of our virtues, and the Christians in our lives will be best in helping us with others. Furthermore, the struggles or experiences we have uniquely as Christians will not be the only struggles and experiences we need to deal with, and so we might need to look outside our Christian circles for help.

In the end, all we can say is this: it is a good idea to at least have some close friends who are Christians, so that they can be friends to us in uniquely Christian ways, by encouraging in us the values laid out in scripture. Without them we might become unequally yoked with people who do not submit to our Lord, which Paul warns against in one of his letters:

Do not be unequally yoked with unbelievers. For what partnership has righteousness with lawlessness? Or what fellowship has light with darkness? What accord has Christ with Belial? Or what portion does a believer share with an unbeliever? What agreement has the temple of God with idols? For we are the temple of the living God… (2 Cor 6:14–16)

Is there a limit to the number of friends we should have?

The second question is whether there is a limit to the number of friends we should have. If good friends make life better, then should we aim to multiply them indefinitely, or is there some stopping point?

There’s nothing intrinsic about friendship that implies an upper bound on the number of friends we can have, but our human limitations do imply one. The fundamental reason for this is that being friends with someone means sharing our lives with them, and we only have so much time to share with others. When we have close friendships with people we will spend time with only them, or in small groups with them, and every moment we do this is a moment we can’t spend with someone else. If we tried to spend time with lots of different people, then we would have to switch between people frequently and see them rarely, in which case it is unlikely that we could ever develop a close friendship with them. Thus, Aristotle says that for friends:

… there is a fixed number—perhaps the largest number with whom one can live together… and that one cannot live with many people and divide oneself up among them is plain… It is found difficult, too, to rejoice and to grieve in an intimate way with many people, for it may likely happen that one has at once to be happy with one friend and to mourn with another. Presumably, then, it is well not to seek to have as many friends as possible, but as many as are enough for the purpose of living together; for it would seem actually impossible to be a great friend to many people. (NE IX.10 1170b32–1171a10)

And later he says:

Those who have many friends and mix intimately with them all are thought to be no one’s friend… one cannot have with many people the friendship based on virtue and on the character of our friends themselves, and we must be content if we find even a few such. (NE IX.10 1171a15–20)

At least in the case of virtue-friendships—which we’ve said are the ones where our friends are most truly “as our own soul”—there is a limit on the number of friends we should have. What the exact number is will depend on us and our friends, but experience says that it’s typically not very high.

We can say something similar for pleasure-friendships, although in these cases the limit may be higher than in virtue-friendships. This is because of what we said earlier, that pleasure- and utility-friendships are based on a small slice of life, and so there is less to share than with virtue-friendships. But, we should caution, they still take up some of our time, and so if we fill our lives with pleasure-friendships then we will likely miss out on the richness of virtue-friendships, including support in tough times and encouragement to become a better person. This difference in the limits for pleasure- and virtue-friendships is likely explains to some extent why we have more friends earlier in life and fewer later in life. As we grow older, the shallowness of pleasure-friendships becomes more apparent, and our tastes become more discerning as we become less enamored with things like popularity.

Utility-friendships differ from the other two in that there is more often an intrinsic limitation on the size of the friendship. It would be strange, for example, to have many personal trainers, or many laundromats that you go to, or many GPs, or many handymen. Typically one (or a few) is enough. But when the friendship doesn’t imply a limitation like this, then the same considerations as we saw of the other two kinds of friendship apply.

When should friends part ways?

The final question we will consider is when two people should stop being friends with one another. It’s clear enough that if someone drastically hurts their friend and does not repent of it, then that would be a valid basis for breaking off a friendship. Indeed, this might even be a basis for breaking up a family, and repentance isn’t even needed in cases that would break up a marriage. We would still need to work our way to forgiveness of the ex-friend who hurt us, but we would not be expected to rekindle a close friendship with them. Assuming that neither friend has severely hurt the other, what are the cases when they should part ways?

In general, friends stop being friends when the basis of reason for the friendship fades away. In the case of pleasure- and utility-friendships, this will happen as soon as the friends are no longer pleasant or useful to one another, or when one of them longer needs the utility other can provide. In the case of asymmetric virtue-friendships, where one thinks they’re in a virtue-friendship and the other doesn’t or where the friends are differently-committed to the friendship, then it might be best to part ways if the asymmetry cannot be addressed.

In the case of true virtue-friendships, it might happen that our friend becomes caught up in the wrong crowd or starts spiralling more and more into vice. We’ve already said that our first responsibility as friends is to help them as best we can, but if they are resistant then at some point they might be beyond help. In all likelihood, such a person would break off the friendship themselves, not wanting to feel judged or finding us a bore. But if not we may need to reevaluate whether we still find them desirable for their own sake or not, and therefore whether we should still be in a virtue-friendship with them. It might happen automatically without us intending, that we start to see them more as a virtue-friend and more of a pleasure- or utility-friend, in which case we might find ourselves in an asymmetric virtue-friendship.

Even in the case where neither friend ceases being desirable to the other for their own sake, it may happen that the friends are unable to share their lives in the way that close friends ought to. If one of them moves to a different country or city, and if they are not able to continue sharing their lives with one another, then over time they may drift apart. Although I should add that this is not the only outcome. Just as distance doesn’t stop family members from being closely related, so too it may happen that two friends are so closely connected that the occasional catch-up is sufficient to keep their friendship going. However, in these cases, we should caution that while distant friends can still make life better, their distance will make them less able to help in tough times or be much a force for making us better. So, having distant virtue-friends should not stop us from making new local virtue-friends.