Character as virtue

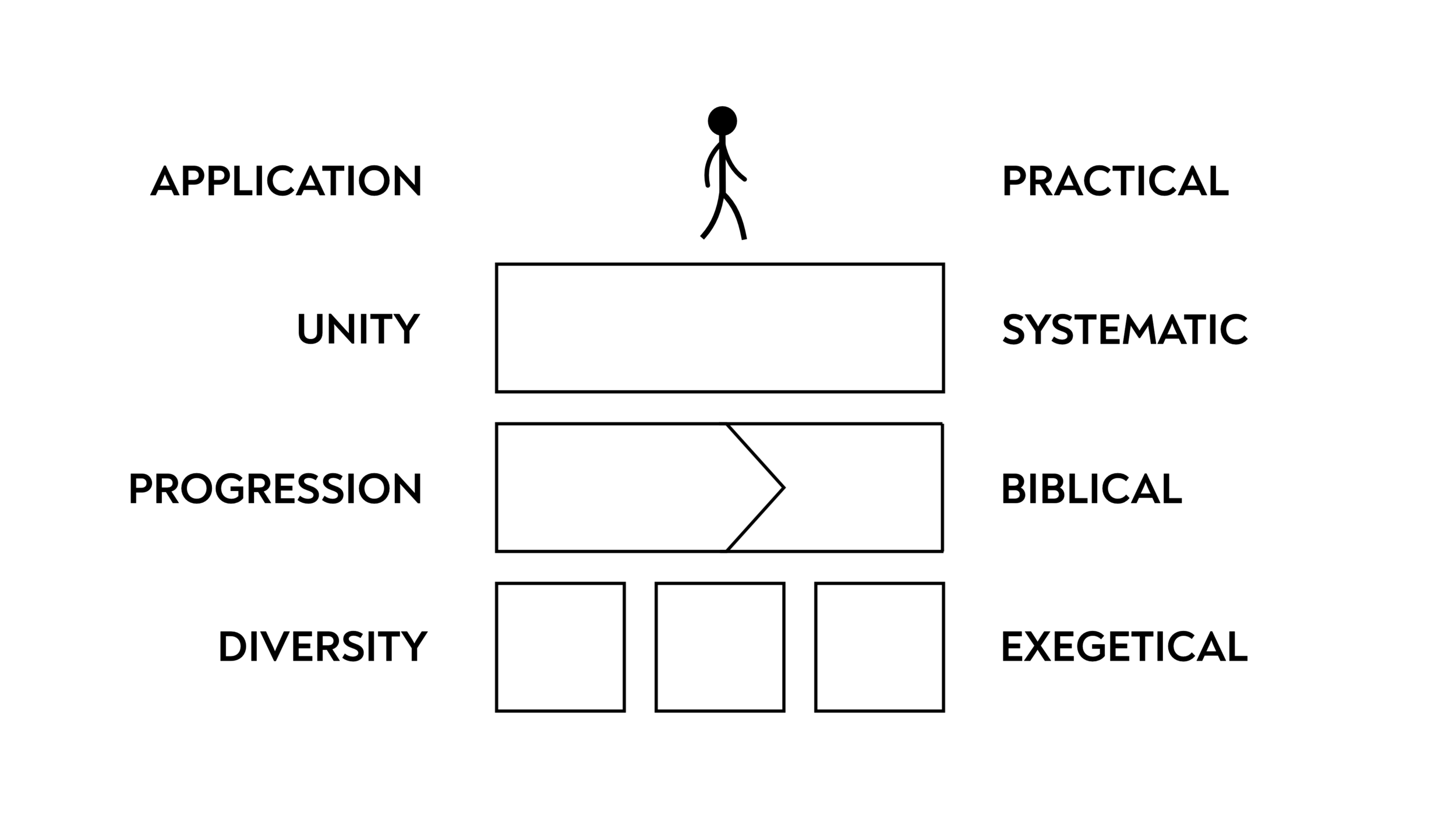

We’re busy looking at practical theology in this module, with a focus on ethics. Last week, Matt introduced us to the idea of practical theology, and how it relates to the biblical and systematic theology we’ve done in previous modules.

Matt also helped us reorient our thinking about how we use the Bible for ethical guidance. In particular, we saw the important role that wisdom plays in living the good life, and therefore what we should be doing to develop ourselves ethically.

Tonight we’re going to consider how the biblical vision of the good life can be supplemented by various ideas from philosophy. In particular, we’re going to see how Aristotle helps us think more deeply about character, virtue, and happiness.

Using philosophical ethics

When we went through systematic theology, we emphasized that doing it properly requires that we combine what we can learn from scripture with what we can learn from nature. God has given us both his word and this world to learn from, and if we want to do so properly we need an approach that can combine insights from both into a single system of thought. Thus, when we looked at creation, providence, simplicity, and eternity, we used philosophy as a tool to supplement—and sometimes even guide—what we could learn from scripture. Since practical theology is more-or-less the application of systematic theology, it shouldn’t surprise us to discover that it works in much the same way.

A brief defence

Now, if you’d like a general defence of this approach, please take a look at the first lesson of our previous module. For now, I will just mention three quick reasons why I think we should include philosophy when studying ethics as Christians.

First, we can’t avoid being influenced by some or other ethical philosophy, and so it’s better to be deliberate in our handling of it rather than simply letting the current tendencies in our culture influence us without us realizing. As GK Chesterton pointed out:

Philosophy is merely thought that has been thought out. It is often a great bore. But man has no alternative, except between being influenced by thought that has been thought out and being influenced by thought that has not been thought out.

Our goal here is to try to think some of that thought out when it comes to living well in God’s world.

Second, we saw last week that wisdom is at the heart of biblical ethics, and much of the wisdom meditation in books like Proverbs and Ecclesiates is based on observations from how the world works. Thus, in using the insights from philosophy we are following the example set by scripture for thinking through the good life.

Third, different philosophical ideas can help flesh out the details of what we’re given in scripture. We’ll see this tonight, as we look at what some philosophers have to say about developing character.

Ethics through the ages

Since before the writing of the New Testament, philosophers have been putting forward various ways of thinking about the good life. Each thinker has their own unique emphases, but we typically group them in terms of what they think living well is primarily about. If a view says that the good life is primarily about following rules, then we call it a “deontological” ethics. If it says living well is primarily about maximizing certain outcomes or consequences, then we call it a “consequentialist” ethics. And if it says it’s primarily about developing a certain kind of character, then we call it a “virtue” ethics. This is not to say that virtue ethics don’t care about consequences or that consequentialist ethics don’t care about rules—it’s just about where the emphasis and starting point is for each theory.

Historically, both Christian and non-Christian thought in the West placed a large emphasis on virtue ethics. This is because we’ve largely built upon the foundation of the Greek philosophers like Plato and Aristotle, and these placed a large emphasis on character when thinking about living well. As we saw in the previous lesson, it’s unsurprising that this was an effective approach for Christian thinkers, since biblical ethics places a big emphasis on character.

Unfortunately, we live in a time and place where virtue and character are not deemed as important as they once were. Around the time of the Enlightenment in the 17th century (2 millennia after Aristotle), virtue and character were displaced in favor of an emphasis on rules and outcomes. Virtue and character were still mentioned in ethics, but did not play as central a role as they had before. Over time, people tended to care less and less about them, to the point where around the end of the 19th century, we had replaced character almost entirely with the non-ethical category of “personality”.

More recently in philosophy, there has been something of a resurgence in focus on virtue and character, but for those of us not in academia, we’ve forgotten how to think about them. This is why we are placing such a big focus on them in this module, as a sort of course correction.

Combining biblical and philosophical ethics

Now, because of the variety that exists among philosophical views on ethics, it’s difficult to give rules for how to combine them with biblical ethics that will apply in every case. Some philosophical systems will be more helpful, others will be less helpful. Some will supplement biblical ethics, others will contradict it. When coming to a particular thinker, the best thing to do is identify places of similarity and difference with biblical ethics, and then use this as a general guide for extracting helpful insights while leaving anything unhelpful behind. It’s very difficult to be entirely wrong about something, so we shouldn’t disregard a thinker just because they aren’t inspired by the Holy Spirit. But we also shouldn’t fall into the opposite error of thinking that they are infallible when in fact they’re not. Of course, this approach requires that we have a good handle on biblical ethics in the first place, so that we can make informed judgements about similarities and differences, which is why we started with that and will continue to unpack it that as we go along.

For this lesson, we’re going to use Aristotle as a worked example. He was a Greek philosopher who has been hugely influential in the Western world as well as being leveraged in later Christian theology. He’s an interesting comparison point when it comes to ethics, because as we we’ll see (1) he agrees with biblical ethics on key points, (2) his approach is different but complementary to scripture, (3) he can help us fill in the details of what it means to develop of our character, and (4) he doesn’t go far enough sometimes. We’ll get through the first two pretty quickly, we’ll spend a good amount of time on the third, and then we’ll close with the fourth.

The importance of wisdom and other agreements

Aristotle agrees with scripture on some fairly big issues when it comes to ethics. For instance, he agrees that what is good for us is a function of our nature as human beings. He believes that there is one supreme God and that the best life is to some extent lived with him. He believes that if we want to live the good life then we need to develop character. And, he agrees that wisdom is critically important for doing this, just as we saw last week with biblical ethics. For instance, he says:

Virtue… is a state of character concerned with choice… this being determined by reason, and by that reason by which the man of practical wisdom would determine it. (NE II.6, 1106b35–1107a5)

This quote also shows that Aristotle agrees with the Bible that wisdom involves both knowledge and action. At the end of the day, life is just too complicated and varied to be captured by a set of rules that apply in every case, and so wisdom is necessary if we want to navigate the complex situations that we come up against.

Inside-out vs outside-in approaches

But an emphasis on wisdom rather than rules doesn’t mean that we can’t still give general guidelines for how to live well. Both scripture and Aristotle agree with this, but they differ in how they go about giving those general outlines. This brings us to the distinction between what we can call “inside-out” approaches and “outside-in” approaches to ethics.

Aristotle approaches ethics from the inside out. He starts by considering the internal psychological workings of human life, such as desire, the role of pleasure, the formation of habits, and how the intellect and will are supposed to work together. Starting with these, he moves outward to the relations that exist between us and others and addresses issues like justice, friendship, and how God fits into the picture. On the first page of his ethics he talks about how good things relate to our desires, but by the last page he’s motivating why the next thing we should think about is politics—which is all about outer relations.

By contrast, biblical ethics tends to approach ethics from the outside in. Throughout the Bible there are descriptions or instructions in terms of our outer relations—like our family, our neighbors, or our friends—and these outer relations are used indirectly to get at what’s going on inside of us when we live well. The law tends to focus on how we treat each other, Proverbs starts with a warning about who we associate with, and both Ecclesiastes and Job start with how the world outside us works before going on to discuss the sort of response and attitude we should have because of that. One of the clearest examples of outside-in thinking is when Jesus says the following:

For no good tree bears bad fruit, nor again does a bad tree bear good fruit, for each tree is known by its own fruit. For figs are not gathered from thornbushes, nor are grapes picked from a bramble bush. The good person out of the good treasure of his heart produces good, and the evil person out of his evil treasure produces evil, for out of the abundance of the heart his mouth speaks. (Luke 6:43–45)

This idea of knowing a tree by its fruit makes an inner reality knowable in terms of how it expresses itself outwardly; whatever the details of the inner workings are, its goodness can be identified from outside.

It’s not difficult to see why the biblical authors would approach things like this. The way we interact with others is visible and tangible, which is why it’s easier to talk about these things as a way of getting at the invisible and intangible things that are going on inside us.

Virtues of character

Notice that in the above quote Jesus doesn’t only talk about good and bad actions, but also good and bad people. We know good people by their good actions, he says, but it’s not simply the actions that make them good. There’s something about the way the person is that makes them good, from which flows the actions we see on the outside. When we start to talk about the kind of person someone is, what we’re talking about is their character.

Character came up in the previous lesson, when we saw that biblical ethics is often more concerned with our hearts than merely with our outward actions. But even though biblical ethics has a lot to say about what a good character looks like, it doesn’t spend as much time breaking it down and telling us about its “internal makeup”. This is where Aristotle and his inside-out approach can help us fill in some of the details. He also thinks the good life involves developing the right sort of character, but because he starts on the inside he ends up spending a lot more time thinking about the structure of character.

According to Aristotle, we should think of our character as the collection of our virtues and our vices. Thus, by studying the virtues and vices that humans can have, we can deepen our understanding of character—what makes character good or bad, and how we become better.

To get us all thinking in roughly the right area, we can start with a short thought exercise. Think about your best friend or someone that you admire deeply, and then ask yourself what it is that you admire so much about them. I suspect we would say things like, “he’s always there for me”, or “she’s very generous”, or “he cares deeply about people”, or “she’s just so kind”. Each of these is an example of a good character trait, or what we call a “virtue”—dependability, generosity, compassion, and kindness. Other virtues would include things such as courage, friendliness, self-control, lovingness, meekness, patience, and studiousness. By contrast, “vices” are bad character traits, such as pridefulness, ill-temperedness, lustfulness, stinginess, absence, and impatience. Your character, we said, is the collection of your virtues and your vices.

Now, in its most general sense, a virtue is some feature that makes a thing work well, and a vice is a feature that makes a thing work badly. Sturdiness is a virtue of a chair, long battery-life is a virtue of a cell phone, and all the examples we just gave are virtues of human character. These are also commonly called “moral” virtues. But humans can also exhibit “intellectual” virtues, which have to do with how we think rather than how we act or feel. Open-mindedness, good judgement, wisdom are all intellectual virtues. I mention these because, in order to fully flourish as a human being, we need both sets of virtues, but because of time the focus of this lesson is the moral virtues. Some of what we say applies to intellectual virtues as well, but not all of it.

What virtue is

So far we’ve listed some virtues, but we haven’t said what it means to have one. At its core, I think we can break it down into at least three elements.

First, a virtue is something that produces action of the relevant kind. Patient people do patient things, courageous people do courageous things. And whether it be giving up money or time, generous people act generously. Virtue produces action of the relevant kind.

Second, a virtue is something that produces action for the right reasons or with the proper motivations. If you give someone money with the expectation that they’ll pay you back, then you’re not being generous; if you spend time with someone solely to win favor with them, then that’s not generosity. Now, expecting repayment or winning favor aren’t necessarily bad things, but they’re not generous motivations either. In order to be generous, you need to give freely and for the sake of someone else. Virtue produces good action for the right reasons.

Third, most complicated, a virtue reliably produces good action for the right reasons. We can understand this in two ways. First, suppose I told you that Alice has just given away R100 to a friend, to help them with a job application. This is certainly a generous thing for Alice to do, but by itself is it enough to make her a generous person? No: for all we know this is the only generous thing Alice has ever done, and the only one she will ever do! Aristotle says that, “one swallow does not make a summer, nor does one day” (NE I.7, 1098a15-20) and we might add that being generous for a short time does not make someone a generous person. In order to be a generous person, you need to reliably do generous things across a long period of time. That’s the first thing. The second thing is that you need to be reliable across a wide variety of circumstances. Imagine Alice was consistent in being generous throughout her life, but only ever to her friends. In this case, Alice wouldn’t have the virtue of generosity, but only an incomplete version of it, which we could call the virtue of generosity-to-friends. In order for her to be a generous person without qualification, she needs to be generous across the wide variety of situations that she faces in life.

So, a virtue is a character trait that reliably leads to good action of a particular kind for the right reasons. Now, I’m not saying that a generous person has to help every time a need arises—otherwise they would go broke in a day and completely exhaust themselves! The point is rather that a generous person exhibits a consistent pattern of behavior, in that they regularly help others in all sorts of situations.

So this is what virtue is, and vice is the opposite. A vice is a character trait that reliably leads to bad action, or at least good action for the wrong reasons. As we said earlier, our character is the sum of our virtues and vices, so you can know someone’s character by how they regularly act. If they have cultivated many virtues then they are a good person living the good life, and if they have cultivated many vices then they are a bad person living the opposite of the good life. But they can also be somewhere in between: if they are not reliably generous or reliably selfish, then they have neither the virtue nor the vice. In this case, the person in this weird twilight state between virtue and vice, with the opportunity for becoming virtuous and the risk of becoming vicious.

The doctrine of the mean

So, living the good life is about developing good character; developing character is about cultivating virtue; and virtue is about reliably performing good actions for the right reasons. But what does that actually look like in practice? Here we hit into a bit of a problem, because the answer is “it depends”. The general shape of a virtue will always be the same, but what it looks like in action will depend on the details of the particular situation we find ourselves in. Generosity is always about giving up time or money for the sake of another—this is its general shape—but how much time or how much money will depend on what we can give, what the other person needs, and various other parameters. This is why when Aristotle talks about virtue, he gives a very general answer, saying that virtue requires that in each case we choose “by that reason by which the man of practical wisdom would determine it.” (NE II.6) We need wisdom to help us judge things on a case-by-case basis, and determine what is appropriate in each case.

Admittedly, this isn’t a super helpful answer. But when we’re studying something, we can’t expect more precision than our subject matter allows, and we’ve already said that life is too varied and complex to be able to lay simple rules that apply to every case. So, Aristotle refuses to give us any. Instead, what he does is give us an outline of what we should be looking out for as we go through life. In general, the principle for moral virtues is this: every moral virtue lies in the middle between two vices, one of excess and one of deficiency. This is called the “doctrine of the mean”, and it’s worth quoting Aristotle’s introduction of it at length:

… it is the nature of such things to be destroyed by defect and excess, as we see in the case of strength and health (for to gain insight on things [we can’t see, such as virtue,] we must use evidence of [things we can see, such as these]); exercise either excessive or defective destroys strength and similarly drink or food which is above or below a certain amount destroys health, while that which is proportionate both produces and increases and preserves it. So too is it, then, in the case of temperance and courage and the other virtues. For the man that flies from and fears everything and does not stand his ground against anything becomes a coward, and the man who fears nothing at all but goes to meet every danger becomes rash; and similarly the man who indulges in every pleasure and abstains from none becomes self-indulgent, while the man who shuns every pleasure, as boors do, becomes in a way insensible; temperance and courage, then, are destroyed by excess and defect, and preserved by the mean. (NE II.3 1104a10–26)

According to the doctrine of the mean, we can classify every moral virtue in terms of three components. Whenever life presents us with a situation, this will lead us to respond, in the form of an action. If this response is excessive or deficient in some way then the resulting action will be vicious, but if it is somewhere in-between these extremes then the resulting action will be virtuous. So, the three components we can use to classify each moral virtue are (1) the response we make that leads to our action, (2) what this response looks like when excessive, and (3) what it looks like when deficient. Excess and deficiency give us the “goal posts” that we need to aim between if we want to hit upon virtue. And the more virtuous we are, the more reliably we will do so.

Consider the virtue of generosity. Let’s say that someone is in need of money, and our response is how much we choose to give them. Giving too little would be stingy, giving too much would be reckless or prodigal (which is why we call him the “prodigal son”). Giving a proportionate amount would be generous. But what is too little or too much? We can’t say in general, because it depends on the details of the situation. But knowing what we’re aiming for does hint what sort of questions we should be thinking about. How much does the person need? How much can we spare? Are we expected to help with everything or only a part of it? And, how much do we trust the person will do the right thing with the money? Based on the answers to questions like these, we’ll get some sense of what’s appropriate, what’s too much, and what’s too little. And the more generous we become, the better we will get at making these sorts of judgments.

Or consider the virtue of dependability. Let’s say that a friend of ours is in trouble, and our response to this situation is the degree to which we’re going to help them. Not helping them enough would be absence, trying to solve everything for them would be overbearing, and helping the right amount is what it means to be dependable. Again, now that we know the goal posts, we can come up with questions we should consider and go from there.

I’ve listed some more examples in the table below.

It’s a worthy exercise to take something you think is a virtue, and try to analyze it in terms of response, excess, and deficiency. Look at Proverbs, or the Sermon on the Mount, or the fruit of the Spirit and see if you can analyze some of the virtues listed there. It can be tricky, but will often give you clarity about that virtue, and lead you to ask the right sorts of questions when reflecting on your actions.

How to acquire virtue

Now that we have a sense of what virtue is, the next question is how we acquire it. After all, if the good life is about virtue, then just knowing about it is not enough. Not everyone who’s good at watching movies is good at making movies, and not everyone who can appreciate a good chair would make a good carpenter.

We’ve said that a virtue is a character trait that reliably leads to action. In other words, virtue is a habit—which is a helpful way to start thinking about how we acquire it. This may seem like a small point, but in fact, shifting our thinking from individual actions to the habits that lie behind them is an important first step when thinking about the good life. If the good life is only about making good decisions according to a set of rules, then our focus would be on those moments when we obviously need to make a difficult decision. The main issue would be the strength of our willpower in these moments, hoping that we could resist temptation and choose well. From the perspective of ethics, there wouldn’t be much for us to do outside of these relatively rare moments.

But once we realize that living well is really about developing habits, then the good life is more like a muscle we need to exercise or a skill we need to practice daily. As Aristotle says:

[We get the virtues] by first exercising them, as also happens in the case of the arts as well. For the things we have to learn before we can do them, we learn by doing them, e.g. men become builders by building and lyre-players by playing the lyre; so too we become just by doing just acts, temperate by doing temperate acts, brave by doing brave acts. (NE II.1 1103a30–1103b2)

Most of our habits, whether good or bad, are formed gradually in the course of the small everyday decisions we make without thinking too much. Generosity is cultivated by the way we treat the car guards we meet every day more than by that donation we make once a year to a charity. Dependability is cultivated by our being there for our friends in the small inconveniences of life more than by the big moments when they desperately need us. On the flip side, a bad temper isn’t defined in a single day, but cultivated through the daily encouragement of anger, when we shout at inanimate objects or kick pillows across the room. And selfishness is grown by the constant choice of oneself over others, even in the small cases where no-one is wronged. As James Clear says:

Every action you take is a vote for the type of person you wish to become. No single instance will destroy your beliefs, but as the votes build up, so too does the evidence of your new identity.

At the end of the day, the vast majority of our lives we live on auto-pilot; and most of the things we do, we do without thinking or only half-thinking. Acquiring virtue is about gradually programming that auto-pilot, so that it can reliably make good decisions for the right reasons, and naturally reflect on the right questions in each situation.

The signs that virtue has been acquired

The last thing to consider about virtues is how we know when we’ve acquired one. It’s easy to tell that we’re performing a particular action because it’s something visible; but our virtues are our invisible dispositions that produce our actions, so they’re a little more difficult to measure.

The most straightforward sign that you’ve acquired a virtue is that you find it easier to perform the relevant good actions for the right reasons. The right questions will pop to mind first, rather than needing you to slow down and force yourself to think through the situation. And the right answers will be intuitive, rather than being something you need to think long and hard about. These are the typical results of mastery of a new skill.

To give an example many of us will be familiar with, we could compare cultivating virtue to learning how to drive a car: initially, when you’re learning, you have to focus on everything you’re doing, because there’s so much to think about that you’ve never had to think about before. But as you get more and more practice, it becomes second nature and it comes to you more easily. I think about this every now and then, because I remember learning how to turn a corner in a car. At the time it was really difficult—you need to slow down, then drop to second gear, then turn, and while you’re turn start accelerating again, all the while watching out for any other cars. But I’ve been driving for more than a decade now, and these days the only thing I think about is which direction I’m turning, not how I’ll do it. The same goes for every other aspect of driving, and every aspect of our characters.

The second sign that you’ve acquired a virtue is that you will take pleasure in doing good things for the right reasons. This is something that distinguishes virtue from skill, since we can have a skill that we don’t take any pleasure in performing, or even that we take displeasure in performing. I still remember one of the first times this occurred to me: a classmate of mine in primary school was really good at swimming, but I was surprised to hear him say that he didn’t really enjoy it all that much. In hindsight, this shouldn’t have surprised me as much as it did, but it goes to show that skill doesn’t always correlate with pleasure. But with virtue, as you grow in it you gradually take more and more pleasure in it. As Aristotle notes:

We must take as a sign of states of character the pleasure or pain that supervenes upon acts; for the man who abstains from bodily pleasures and delights in this very fact is temperate, while the man who is annoyed at it is self-indulgent, and he who stands his ground against things that are terrible and delights in this or at least is not pained is brave, while the man who is pained is a coward. (NE II.3 1104b4–10)

After all, people often do bad things because they bring pleasure and avoid doing the right thing because it’s painful. So, unlike with skill, pleasure and pain are closely connected to how we behave and the motivations we have for behaving, and therefore they are a good measure of whether we have acquired a particular virtue—or a particular vice.

The place of happiness in the good life

That brings us to the end of what we’re going to say on virtue. Hopefully, this introduction has shown how it can be a helpful tool when filling out some of the details of the good life. When scripture holds up values for us to follow, we should ask how they’re related to virtue and what that means for how we should pursue them. We’ll see a bit of what that looks like next week, when we look at the topic of friendship.

But considering everything we’ve said, I’m sure at least some of us are thinking, “this whole good life thing is really hard!” It’d be much easier if it were just about the big decisions we make every now and then in life; if a compelling argument or a convicting sermon were all that was needed for us to become more Christ-like. But what we’ve been saying is that the good life is more about the gradual development of character, through the slow cultivation of virtue; we’re saying that a sermon is not enough, but that you’ve got to find a way to regularly put virtue into practice if you ever want it to take root in your life.

It is difficult, but it’s also worth it. As far as Aristotle is concerned, cultivating a life of virtue is what it means to be truly happy. Of course, happiness requires a certain level of comfort, where at least our basic needs are met, but we shouldn’t confuse this with happiness itself. Happiness is something we desire always for its own sake and never for the sake of something else; and once we reflect on what that must look like for humans, we see that it can’t be any of the “obvious” answers that people give. It can’t be wealth or power because these are only valuable for doing other things, and miserable people can be wealthy or powerful; it can’t be honor or praise because these aren’t about our life, but about other people’s opinion on our life, which can be mistaken; and it can’t be only bodily pleasure or bodily goods (although it might include these) because we are capable of more as humans than we are with just our bodies.

After rejecting these common views, which were as common then as they are today, Aristotle argues that happiness must be about living in accordance with the intellectual and moral virtues. Such a person would reliably make the right decisions, at the right times, in the right ways, for the right reasons, and take pleasure in doing so. This does sound like happiness, or as we’ve been calling it, the good life.

But centuries later, the Christian theologian Thomas Aquinas argued that this account of happiness doesn’t go far enough. You see, while Aristotle believed in one God and thought that the happy person would spend much of their time contemplating God, he didn’t know that God had made it possible for us to live with him. So, when Aquinas was developing Aristotle’s system, he added in this missing piece. He did so by introducing a distinction between two kinds of happiness.

First, there’s natural happiness, which is what Aristotle was talking about—life lived in accordance with all the moral and intellectual virtues. This is the most we can achieve with the capacities God has given us humans, although even this is made difficult and even impossible because of the influence of sin in the world.

Then there’s supernatural happiness, which extends natural happiness in two ways. First, it’s based on God himself living with us. For now he lives with us through the Holy Spirit in an incomplete way, while we’re still weak and struggle against sin. Later, in the new creation, we will live with him completely, without any burden of sin remaining. As Paul says:

For now we see in a mirror dimly, but then face to face. Now I know in part; then I shall know fully, even as I have been fully known. (1 Cor 13:12)

Since supernatural happiness depends on God’s living with us, we could never achieve it by our own powers, even if we were sinless. No matter how hard we tried, we could never make God live with us—he needs to choose to share himself with us.

The second way that supernatural happiness extends natural happiness is that God gives us the three theological virtues: faith, hope, and love. These three virtues are added to the intellectual and moral virtues to help us live with God now, and when the new creation comes, faith and hope fall away but love continues to help us live with him in eternity. Paul speaks of these three virtues in the next verse:

So now faith, hope, and love abide, these three; but the greatest of these is love. (1 Cor 13:13)

They are called “theological” virtues because each of them has to do primarily with God. We have faith in God and what he has achieved in the gospel; in hope we look forward to Jesus’s return and the fulfillment of God’s promises to make everything new; and we love God above all as our creator, and his creation because of that. Again, like God’s life with us, these three theological virtues are given by God’s grace, and are not things we could have acquired by our own efforts with the powers he has given us as humans.

So, supernatural happiness is the good life lived with God in accordance with all virtues—including the theological ones. Unlike natural happiness, even if we were sinless we would not be able to achieve supernatural happiness for ourselves, because it depends entirely on God’s grace towards us.

Postscript on using modern psychology

Modern psychology has given us loads of great resources on a number of the things we covered in this lesson. Typically, it tries to be as neutral as possible when it comes to questions of morality and ethics, but now that we have this framework for thinking about character we can read these books and leverage their insights to help us develop ourselves ethically in accordance with what is revealed in scripture.

Some books you might be interested in are Atomic Habits by James Clear, The Character Gap by Christian Miller, and Practical Wisdom by Barry Schwartz and Kenneth Sharpe.